Hyvee Connect is the official login portal for Hy Vee Company employees using the Hy Vee Huddle. Hy-Vee Connect is a portal specially developed for all employees who work in the company. That way they will have access to all the details about their work and other compensation. The hotel’s daily work report is also updated, so they know how your stay at the company is going.

Hyvee Connect is the official login portal for Hy Vee Company employees using the Hy Vee Huddle. Hy-Vee Connect is a portal specially developed for all employees who work in the company. That way they will have access to all the details about their work and other compensation. The hotel’s daily work report is also updated, so they know how your stay at the company is going.

Or

Hy-Vee Company operates fitness studios, gas stations with convenience stores, and full-service restaurants at some of its properties. It’s a fantastic online store where you can buy what you need. There are over 10,000 satisfied employees at HyVee. Before starting the Hyvee Connect enrollment process, I would like to talk about some of Huddle Hyvee’s benefits briefly.

Steps For Login At Hyvee Huddle

The steps are really very simple to successfully login to the Hy-Vee portal. They are as follows: –

- You must first open your web browser and access www.hy-vee.com.

- Then enter your username and password in the field.

- Make sure you have a valid username and password.

- Now click on the LOGIN button, and you will have access to your account.

Hyvee HuddlePortal

Hyvee Huddle, I am talking about the Hyvee Huddle login and login portal for employees today. Employee Benefit: If you want to enjoy all the benefits, you must go through the Hyvee Huddle login process. Two hundred forty-five locations of this company in the USA. Hyvee Huddle Connection – Hyvee Employee Connect Portal in progress.

Requirements for Login

- The official web address to login.

- Valid username and password.

- Web address compatible internet browser.

- The smart device has access to an Internet connection and supports the same email address.

Steps To Register At Huddle.hy-vee.com

Employees who work at this company enjoy many benefits when they create a Hy Vee Employee account online. The online employee account registration process offered by Hy Vee is quite simple. This portal is designed to provide employees with easy access, a good experience, and easy access to benefits and services.

The online employee account registration process offered by Hy Vee is quite simple. This portal is designed to provide employees with easy access, a good experience, and easy access to benefits and services.

- Follow these quick steps to create an account online.

- Go to https://huddle.hy-vee.com/ to visit the official Hy Vee login portal.

- Hover your cursor over the login button and select the “Create an account” option

- Enter your name, date of birth (mm/dd /yyyy), the last four digits of your social security number

- Then resolve the security check captcha and follow the rest of the process to create an account.

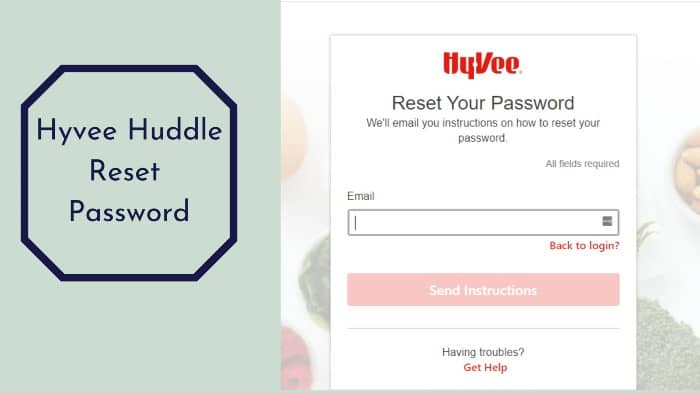

Resetting Credentials For Hyvee Huddle Employee Login

Hyvee Huddle Login Process Forgotten password system that provides a step-by-step process.

- Hyvee Huddle App-Connect can be accessed through https://huddle.hy-vee.com/ in your browser. There is a difference between this link and the previously shared Hyvee Huddle login page.

- Click on the “Forgot your password?” on the Huddle Hyvee Login page

- You will be redirected to the “Reset your password” page.

- Enter all requested information as requested, such as B. Employee ID, last four digits of your social security number, new password, confirm password.

- After entering your data, click “Go.”

- You can now re-enter the Hyvee Huddle Employee login page with your new password.

Benefits Of The Huddle Hyvee Login Account Process

- It has a great online store that has everything you need. Obviously, they have a lot of people working for them, and they need a complete platform to manage their team, keep them up to date, keep up with their work and make it easier. Hyvee Huddle App-Connect gives them access to everything they want to ensure greater efficiency, more data security, and better communication across the enterprise.

- Employee wellness programs include learning healthy lifestyle skills to motivate them to lead by sharing knowledge about wellness and health issues through Huddle Hyvee login.

- If an employee wants to move across state lines, he receives financial assistance.

- Employee Discount: Employees are entitled to a 10% discount on in-store Hyvee Huddle purchases and 20% off dinner orders at their restaurants. You also receive gift cards and fuel economy benefits.

Furthermore, there are several opportunities for Huddle Hyvee Login.

- Various tax saving plans

- Paid leave and free time

- They offer excellent insurance benefits to employees and their families, including life insurance, medical and dental care, drug insurance, and short-term disability from work.

- Rewards and Recognition: Hyvee recognizes and honors its employees for their performance and for achieving the goals that motivate them.

- You have a 401K-compatible business with pension benefits and profit-sharing.

- Other financial benefits of the business, such as loans, bonds, bonds, etc.

Benefits of the Hyvee Huddle Connect portal

- Employees can customize it to their needs.

- Know the service structure for a given month.

- All online payments can be easily managed.

- The salary situation is updated on the portal.

- A progress report is available.

| Official Name | Hyvee Huddle |

|---|---|

| Country | USA |

| Managed By | Hyvee Huddle |

| Portal Type | Login |

| Registration | Requirements |

About Hyvee Huddle

Hyvee Huddle is an American supermarket chain owned and operated primarily in the Midwestern United States. The company was founded in 1930 by Charles Hyde and David Vredenburg in Beaconsfield, Iowa, and operates more than 265 stores in eight Midwestern states: Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.

It specializes in offering a variety of food and general merchandise, including fresh produce and meats; dry and dairy products; health and beauty products; photographic processing; bakery products; and a delicatessen service with chefs on-site at some locations.

Hyvee Huddle is a supermarket chain with at least 240 supermarket agencies. They are located in the American Midwest in Missouri, Nebraska, South Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska, Kansas, Lowa, and Wisconsin. Huddle Hyvee was founded in 1930 by Charles Hyde and David Vredenburg. Headquartered in West Des Moines and Iowa, the company employs more than 85,000 people. With annual revenues of $9.3 billion, Hy-Vee is one of the top 50 private companies in the United States.

Hyvee Huddle, also known as Hyvee Connect, is the official web portal for Hyvee employees. You must go through the Hyvee Huddle application process if you want to make the most of your employee benefits. This company is a supermarket chain based in the United States, with a presence in more than 245 locations in the United States.

Huddle Hyvee Kronos

The Hy-Vee Kronos Employee Satisfaction Index™ is a tool to measure employee satisfaction. An organization’s toolkit includes one of the most powerful ways to improve its workforce.

It is essential to know what motivates employees to help with retention and engagement, increase productivity, create business growth and provide an enjoyable shopping experience. The Kronos Employee Satisfaction Index™ can help pinpoint those areas and measure how to improve them.

Hyvee Connect Troubleshooting

If you are facing any issues with the logging account at Hyvee Connect, then you should check out the following things:

- Re-enter your login ID to make sure your email address and password are spelled accurately. Also, remember that passwords are case-sensitive.

- For accessing your account, cookies should be accepted. So, you must check out the browser settings to make certain that you are accepting the cookies.

- This issue can also be caused if Javascript is disabled on your computer. It is only influenced when you are using the enter or return key on the keyboard of your computer. So, you should use the mouse to click on the sign-in button. It works despite being javascript disabled or not.

- You can also disable your firewall and then try to login into the account. The firewall might be the issue restricting you from logging into the Connect Hyvee account.

- In your browser, do not forget to clean all of your caches.

* Hence, if you have tried all the above steps and still require assistance for logging into the account. Then, you can contact Hyvee customer Care.

Hyvee Contact details

To solve your problems related to Hyvee Connect, you can contact them in the following ways.

Hy-Vee Customer Care Number: (800) 772-4098

Communications Department number:

(515) 559-5770 (for media inquiries)

Email Id (Product Inquiry): [email protected]

Website: www.hy-vee.com

Corporate Office Address: Hy-Vee, Inc. 5820 Westtown Parkway West Des Moines, Lowa

Frequently Asked Questions

How do you make a Hyvee Huddle account?

The first thing you need to do is register as an “Online Access Associate” or AA. You’ll be asked to log in to your Hyvee Huddle account using your Facebook email address. You’ll also need to provide your Hyvee Huddle employee email address and a valid phone number.

Do Hyvee employees get a discount?

Employees receive a 10% discount on Hy-Vee purchases in the store and a 20% discount on dinner orders at our restaurants.

What if I forget my password?

On the Hyvee Connect login page, there is an option to retrieve the password. You can click on the “Forgot password” link and follow the instructions. You can also refer to this article for the step-by-step guide.

Conclusion

To conclude things up, I would say HyVee Huddle is basically a login portal just for their employees. It provides a lot of benefits to them including discounts at the stores. I am assuming I have successfully answered all of your queries. If you still have one, feel free to comment. Hyvee Huddle is a good place to start your professional career, and hence we hope this look into the process of logging into the Hyvee Huddle login page has all the necessary information you need to avail yourself of all the benefits that this company has to offer.

Having the Hyvee HUddle employee portal is essential in today’s growing businesses. The Hyvee huddle login page helps to centralize and streamline information, instructions, comprehend company policies, increase employee engagement, build better relationships by offering transparency about the company. Hyvee has supermarkets located in several states across the US, such as Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Iowa, Illinois, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. Hyvee provides career opportunities to those who are interested in being part of their organization. One can log in to their website and go to the career tab to search for different jobs available, including part-time and full-time, and their Hyvee Huddle App processes.